It is not possible to go very far back in the history of Lincoln County, although our introduction has shown that prehistoric times in this section of the country must have been full of interesting events. We have seen that with its superior advantages for food, war and sport it was the favorite stomping ground of several tribes of Indians. It was claimed by more than one tribe, even after it had become government land by treaty. The Pawnees, especially, still considered it theirs and thought they had a right to gain their living from it by raids.

The first white man on record to visit what is now Lincoln County was Bourgmont and his party in 1724. His line of march has been traced through the county going from east to west. Pike and his party came through in 1806. His line of march extended from the north, and the two routes intersected about the place where Lincoln Center now stands.

In the fifties hunting parties going up the Saline and Solomon Rivers operated in the territory which is now Lincoln County. Few of them left any record of their findings or their experiences.

Some of Mr. Mead's adventures appeared in Vol. IX of the State Historical collections from which the following quotations are taken:

"There was a battle fought on the plains north of the Spillman Creek in June, 1861. The Otoe tribe from the north, with their families and a letter from their agent, came down for a big hunt. They camped in the valley along the creek. The Cheyennes found them and sent three or four hundred warriors to drive them out. The Cheyennes were afraid to charge the camp as the Otoes had guns. Both sides fought on horseback with bows and arrows and after the battle arrows could be pic ked up everywhere. In one instance two young men rushed together at full speed, seized each other with their left hands, stabbing with their right till both fell dead without releasing their hold. The Otoes finally retreated down the river to my ranch with scalps, ears, fingers and toes of their enemies, trophies of the fight, tied on poles.

"Once I left a young fellow at a camp I had established while I went over to Wolf Creek to hunt for a few days. On returning I found my man hidden out in the brush nearly frozen, with nothing to wear but his under clothes. Two Indians came along with some stolen horses, saw he was scared, made him cook all they could eat then took off his clothes or whatever else they wanted and leisurely packed their ponies. Back of the camp shelter was my young man with two loaded guns hid under some skins. He was too badly scared to use them. He could have gotten away with both Indians, but he lacked grit.

"On another occasion (December, 1861), I established a camp on Spillman Creek and after collecting a quantity of furs left one man in the camp and went to hunt with my other man and team. It was very cold and snow deep. In a day or two the man I had left came to my camp; said he heard shooting around, was scared and skipped in the night. I drove back and found my camp plundered and a big trail in the snow leading down to the river. Directing my men to follow I started after them on my pony. In a few miles I saw them ahead on foot. Each one had a big wolf skin of mine hanging down his back, a slit in the neck going over his head. There were thirty-three of the party. I followed them unseen for some distance and saw I could not possibly get around them as my pony could hardly stand, her feet were so smooth; but I had to get to my ranch ahead of them, so I rode into them and was surrounded and captured. I found they were a party of Sioux on marauding expedition, some of them, the most villainous-looking being I ever saw. I gave them a good talk, let on I was glad to see them, proposed we all travel together to which they agreed, had a jolly time for half a day, by which time I had so ingratiated myself with the chief who was a fine fellow, that I was allowed to go on alone. Our conversation was carried on in sign language. I had two men at the ranch and my men with the team got in that night. The Indians came to my place the next morning and built a fortified camp in the timber back of the house. I treated them nicely, gave them tobacco and got all my furs back except an otter skin."

"Uncle Mike" Sterns, as he is familiarly known here, used to hunt in this country with Uncle Tom Boyle, Ade Spahn, and a man by the name of Dean, in fifty-eight and fifty-nine. He says that the Moffit ranch house was located about 150 yards down the Saline River from Rocky Hill Bridge on the north bank. The evacuation may be seen there at this time.

On one of these hunting trips the party camped near the mouth of Beaver Creek under a large oak tree that is familiar to all of the old settlers and on going to the creek for water found it dry. Spahn, being an old hunter, led the party up the creek very cautiously and when near where the Dan Day's barn now stands, they came upon a beaver dam where several hundred beavers were busily engaged in enlarging it. Uncle Mike says that it was one of the most beautiful sights he has ever seen.

On another of these hunting expeditions they pitched their camp on the Elkhorn bottom south of Rocky Hill. One of them carelessly threw a quarter of buffalo meat on the picket pins. That night when they staked the horses out with the pins the wolves were so ravenous that they gnawed the pins to pieces, the horses escaped and they never recovered them. One of the number walked to their home in Salina and brought up a team of oxen with which they continued the hunt. On this trip they saw some wolves surround a cast off buffalo and make a circle around him with relays and after chasing him till he was exhausted the hamstringed him and devoured him. this took place around the bluff near where Sam Weigert now lives, southeast of Lincoln.

At one time when camped on the J.W. McReynolds farm in what is now Franklin township, the others of the party went away for the day, as was their usual custom, and left Mr. Sterns in charge of the camp. A party of Indians came up and asked for coffee. He refused to get it for them and after repeatedly asking for it they grew angry and one of them picked up a loaded musket, cocked it and placed the muzzle at his breast. He then pointed to the bucket and to the spring up the hill and told them to go. He did so, and upon returning found the Indians gone and all of the camp supplies stolen.

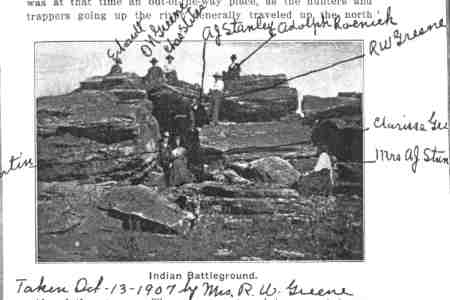

The accompanying illustration is the scene of a battle-ground of the Potawatomie and Pawnee Indians, on Bullfoot. Indian bones were found in the cave shown in the picture and various opinions have been advanced as to how they came there. Mr. A.F. Schemerhorn says in a letter:

"As to the battle between two Indian tribes on Bullfoot, I went over there in 1867 and gathered up a sack full of skulls and gave them to Dr. T.B. Fryer then post surgeon at Fort Harker, and nearly every skull had a bullet hole in it, showing that they were killed by bullets and not with arrows. It was generally believed then that those Indians were killed in a fight with some buffalo-hunters in 1865, I think on Beaver Creek. I think Dan Day now owns the place where the fight occurred. As it was the custom of the Indians to bury their dead by placing them upon scaffolds in some out-of-the-way place and on some high point generally, we supposed they carried their dead from the fight on Beaver Creek over to the point of the rocks on Bullfoot, which was at that time an out-of-the-way place, as the hunters and trappers going up the river generally traveled up the north side of the stream. There was no travel to amount to anything on the south side of the river when I went there in 1867."

Mr. Ferdinand Erhardt, who came to live on Bullfoot in 1867, found a number of skeletons in the cave before mentioned but gives a different explanation.

One day in 1868 Mr. Erhardt was walking along the ridge on the south side of Bullfoot when his dog, prowling among the rocks, came up with a skull. Mr. Erhardt followed the dog back and found an open cave filled with Indian skeletons. He reported his find to Fort Harker, and the soldiers sent a conveyance to remove the skeletons to that place. There were sixteen whole skeletons in the cave, and they were sufficiently preserved to be moved without going to pieces. Mr. Erhardt at that time shared the belief spoken of by Mr. Schemerhorn, namely, that these were the remains of Indians killed by the Moffit boys on Beaver Creek.

But about the year 1880 a band of Pottawatomie Indians camped on Bullfoot and laid out the battle-ground for Mr. Erhardt, and also left the story of the affray in characters on the wall of the cave. It seems that the Pottawatomies and Pawnees had been quarreling about their hunting-ground. The Pottawatomies drove this band of Pawnees in from the west, who, being hard pressed, took refuge in this cave and were massacreed by the Pottawatomies. A Pottawatomie was killed by a Pawnee who shot up from the cave. Those who do not believe that such a battle occurred, and that this was a burying-ground instead of a battle-ground, base their opinion on three things.

First, that the Indians were killed by bullets and not by arrows.

Second, that there were no remains of horses found near the place, and that Pawnee ingenuity would scarcely permit them to take refuge in such a death-trap as this cave proved to be.

Third, that both the Pottawatomie and the Pawnee Indians were peaceful and never had any fights.

The writer is inclined to credit the story of the battle. It was learned by Mr. Erhardt direct from the Pottawatomie Indians themselves. Mr. J.R. Mead is authority for the statement that in the year 1861 a large band of Otoes who camped on the Spillman were armed with guns. So the Pawnees and Pottawatomies might have had them two years later.

Indians were often, but by no means always, mounted on horses. According to the record left on the rocks the pursuing party was mounted. Mr. Sol Humbarger says the Pawnees were likely on one of their thieving expeditions on foot. They were driven in to the rocks from the north or northwest.

The fact that their enemies were mounted and they were not will probably account for the Pawnees taking refuge in the first stronghold which presented itself instead of choosing a better place to defend.

The Pottawatomies that camped near the battle-ground in 1880 had an interpreter with them, who talked with Mr. Erhardt.

Authorities do not agree on the peaceful qualities of these Indians, and Mr. Mead says in a letter:

"I left in the spring of 1863, so I know nothing personally of the battle between the Pottawatomies and Pawnees. Usually the Pawnees did not wish to fight."

He says in another place:

"These raiding parties of Pawnees were the especial objects of hatred of all the tribes of the plains both north and south, who fought and if possible killed them wherever found."

THE MOFFIT BOYS

In spite of the fact that the country up the Saline River was not considered safe, a settlement was attempted in 1864 which ended disastrously. In March six persons, Charlie Chase, William Chase, Marion Chase, and John Moffit, Flave Moody and an unknown party, who wrote the story for the "Salina Journal," started westward from their camp near where the Saline bridge now stands; to start a settlement on Spillman Creek. They halted and pitched their camp between Beaver Creek and the Saline River, in the second bend below the mouth of the Beaver. This camp was blown up by the explosion of a keg of powder. The boys then built a log-house and stable. Charles Chase and John Moffit went to Salina for provisions. During their absence the rest of the party had to live on parched corn. After three days of this exclusive cereal diet Flave Moody and Marion Chase started to walk east and the other two stayed by the goods. When the provisions arrived they baked biscuits and bachelor-like forgot to put either soda or baking powder in them. The next move was to buy three cows. They had four horses and one yoke of oxen. Although they had not filed on land they fenced in and planted twenty acres of corn. About the last of May they were driven off by an Indian outbreak. they all arrived in safety at their former camp near the Saline bridge.

About July 1, against all protests, John Moffit and his brother Thomas, with a Mr. Hueston and Mr. Taylor, came back to the ranch. In August, while out on a buffalo hunt, they were surprised by Indians. Settlers who lived about Salina fail to agree in regard to the particulars of this incident. The following is a part of an official report to the Government from the headquarters of the Eleventh Volunteer Cavalry at Salina by Capt. Henry Booth, of Company L:

"Saturday evening, August 6, 1864, four men, two men (brothers) Moffit, one Taylor, and one Hueston, started from their ranch to kill a buffalo for meat, taking a two-horse team with them. Upon reaching the top of the hill about three-quarters of a mile from the house, the Indians were discovered rushing down upon them. the horses were turned and run toward a ledge of rock where the men took position. They appear to have fought desperately and must have killed several Indians, but one of the scalps was left on a rock close by. the horses were both shot through the head. This was probably done by the ranchmen to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Indians. The wagon was burned. the Indians made a descent upon the house in which were an old man and a woman. the man shot one of the Indians through a hole in the wall where-upon they all fled. they judge the number of the Indians to be about one hundred. the Indians retreated up the Saline River."

There is a letter written to Robert Nichol Moffit, of Illinois, by his brother John, dated May 13, 1864, which says:

"We came here March 16. We are twenty-five to thirty miles from Salina up the Saline River. We are now thirteen miles from the nearest house. We put up a stable thirty-five feet in length and a house twenty-two feet of logs."

This ought to prove that the Moffit boys really had a house and mot merely a dugout. the writer to whom we are indebted for the account of the trip in the early spring, says they built a log house and stable. he also says that the woman in the house was Mrs. Hueston, and that she had her two children with her at the time.

They stayed all night in the house, and all the next day watched for Indians. The second night they dug a hole under the back of the house and escaped without coming out at the door. They wandered all night on the Elkhorn and the next morning found their way to the settlement.

A party of twelve men went to look for the bodies and found them in the place described. There was sixteen arrows in John Moffit and fourteen in Tom. The bodies were temporarily buried on the scene of the battle.

The place of the tragedy is described as being the rocky ledge upon the northeast quarter section nine, township twelve, range seven in Elkhorn township of what is now Lincoln County.