CHAPTER IV.

THE DELAWARES.

THEIR WARS ON THE PAWNEES - AS IRVING SAW THEM - CIVILIZATION'S ADVANCE AGENTS - VISITED BY PARKMAN - NOT GIVEN ALONE TO FIGHTING - THE DELAWARE CHIEFS - THE DEATH OF CHIEF KETCHUM - THE LAST OF A NOBLE RACE - THE TREATY OF 1866.

William Penn found the Delaware Indians dwelling peacefully in the valley of the Delaware river, and their council fires blazed on the site of Philadelphia. He cultivated their acquaintance and purchased much of their lands. They called themselves Lenni Lenape (Original Men, of Pre-eminent Men.) The French called them Loups (wolves).

In 1726 the Delawares refused to join the Iroquois in a war against the English. Finally they were driven west of the Allegheny mountains. That was the beginning of their migrations. Near the close of the Revolution a large number of the Delawares were massacred by Americans. The remnant of the tribe dwelt temporarily in Ohio, and in 1818 migrated to southwest Missouri, for twelve years occupying lands near Springfield and along the James Fork of White river.

The coming of the Delawares to Kansas was in 1829. Their new reservation, which they occupied for thirty-eight years, not only included nearly all of Wyandotte county but stretched beyond into Kansas with an outlet to the Rocky mountains. This was their dwelling place until 1867 when they gave up their lands and went to the Indian Territory to live among the Cherokees.

At one time, when the Delawares refused to join the Iroquois in a war against the English, they were stigmatized as "women," the inference being that they were too cowardly to fight. But that is not their record in Kansas. They indeed were quite warlike and it is written that there was not one coward among them. From their reservation here at the mouth of the Kansas river they went out to war against all the tribes on the plains and even beyond the Rocky mountains. An instance which serves to illustrate their fighting qualities is disclose in the burning, in 1832, of the Great Pawnee village on the Republican river and of the exodus shortly after, of the remnant of the Pawnees to another reservation. Commenting on the Delawares William Elsey Connelley, the Kansas writer of history, says: "Think of the audacity of this little nation of Delawares! There could not have been then more than five hundred warriors in all the tribe - perhaps not so many. When Pike visited this Pawnee village and made the inhabitants haul down the Spanish flag and put the American flag in its place, he estimated that there were more than six thousand Pawnees living there, having more than two thousand warriors engaged with other tribes in fierce wars; and larger villages were not far away. But their famous village was burned, Pike or no Pike, flag or no flag, by these fierce children of the Turtle, a portion of whom were living then in what is now Wyandotte county. The secretary of the State Historical Society has celebrated, on the site, the raising of the American flag on Kansas soil. He should inscribe on his monument, there erected, that the great village was destroyed by a little band of warriors living at the mouth of the Kansas river. Indian annals do not record the account of a more daring deed."

Washington Irving gives an interesting account of the Delawares in writings of his tour of the prairies in 1832. They were then widely scattered over the plains. Irving says:

"The conversation this evening, among the old huntsmen, turned upon the Delaware tribe, one of whose encampments we had passed in the course of the day; and anecdotes were given of their prowess in war and dexterity in hunting. They used to be deadly foes of the Osages, who stood in great awe of their desperate valor, though they were apt to attribute it to a whimsical cause. 'Look at the Delawares,' would they say, 'dey got short leg - no can run - must stand and fight a great heap.' In fact, the Delawares are rather short-legged, while the Osages are remarkable for length of limb.

"The expeditions of the Delawares, whether war or hunting, are wide and fearless; a small band of them will penetrate far into these dangerous and hostile wilds, and will push their encampments even to the Rocky mountains. This daring temper may be in some measure encouraged by one of the superstitions of their creed. They believe that a guardian spirit, in the form of a great eagle, watches over them, hovering in the sky, far out of sight. Sometimes, when well pleased with them, he wheels down into the lower regions, and may be seen circling with widespread wings against the white clouds; at such times the seasons are propitious, the corn grows finely, and they have great success in hunting. Sometimes, however, he is angry, and then he vents his rage in the thunder, which is his voice, and the lightning, which is the flashing of his eye, and strikes dead the object of his displeasure.

"The Delawares make sacrifices to this spirit, who occasionally lets drop a feather from his wing in token of satisfaction. These feathers render the wearer invisible, and invulnerable. Indeed, the Indians generally consider the feathers of the eagle possessed of occult and sovereign virtues.

"At one time a party of Delawares, in the course of a hold excursion into the Pawnee hunting-grounds, were surrounded on one of the great plains, and nearly destroyed. The remnant took refuge on the summit of one of those isolated and conical hills which rise almost like artificial mounds, from the midst of the prairies. Here the chief warrior, driven almost to despair, sacrificed his horse to the tutelar spirit. Suddenly an enormous eagle, rushing down from the sky, bore off the victim in his talons, and mounting into the air, dropped a quill-feather from his wing. The chief caught it up with joy, bound it to his forehead, and, leading his followers down the hill, cut his way through the enemy with great slaughter, and without any one of his party receiving a wound."

First among the advance agents of civilization to come into Wyandotte county were the Chouteau brothers, Frenchmen, who built trading houses in 1828 and 1829 among the Shawnees and Delawares. They were licensed traders. One of the agencies was on the south side of the Kansas river opposite the Indian village of Secondine, afterwards Muncie. It was conveniently located for handling the Indian trade from the trails that led out into Kansas territory, and later at the ferry where a military road crossed the Kansas river and led to Fort Leavenworth. It was at Secondine, across the river from the Chouteau trading house, that Moses Grinter, the first white settler, established his residence. The Reverend Thomas Johnson, a Methodist missionary who established a mission school among the Shawnees in 1829, in May, 1832, crossed the Kansas river and established a Methodist mission school among the Delawares near the present village of White Church. He was followed, in 1837, by the Reverend John G. Pratt, who established a Baptist mission among the Delawares which he conducted for many years. He printed hymn books in the language of the Indians and, like Mr. Johnson, was a powerful factor in the education and civilization of the Delawares.

Parkman, in his "Oregon Trail," gives us a glimpse of the Delawares, their Wyandotte county reservation and the military road as he saw them in 1846. He writes: "A military road led from this point (the Lower Delaware Crossing, at the lower end on Muncie bottom) to Fort Leavenworth, and for many miles the farms and cabins of the Delawares were scattered at short intervals on either hand. The little rude structures of logs, erected usually on the borders of a tract of woods, made a picturesque feature in the landscape. But the scenery needed no foreign aid. Nature had done enough for it; and the alternation of rich green prairies and groves that stood in clusters, or lined the banks of the numerous little streams, had all the softened and polished beauty of a region that had been for centuries under the hand of man. At that early season, too, it was in the height of its freshness. The woods were flushed with the red buds of the maple; there were frequent flowering shrubs unknown in the east; and the green swells of the prairies were thickly studded with blossoms.

"Encamping near a spring, by the side of a hill, we resumed our journey in the morning, and early in the afternoon were within a few miles of Fort Leavenworth. The road crossed a stream densely bordered with trees, and running in the bottom of a deep woody hollow. We were about to descend into it when a wild and confused procession appeared, passing through the water below, and coming up the steep ascent towards us. We stopped to let them pass. They were Delawares, just returned from a hunting expedition. All, both men and women, were mounted on horseback, and drove along with them a considerable number of pack mules, laden with the furs they had taken, together with the buffalo robes, kettles, and other articles of their traveling equipment, which, as well as their clothing and weapons, had a worn and dingy look, as if they had seen hard service of late. At the rear of the party was an old man, who, as he came up, stopped his horse to speak to us. He rode a tough, shaggy pony, with mane and tail well knotted with burrs, and a rusty Spanish bit in its mouth, to which, by way of reins, was attached a string of rawhide. His saddle, robbed probably from a Mexican, had no covering, being merely a tree of the Spanish form, with a piece of grizzly-bear's skin laid over it, a pair of rude wooden stirrups attached, and, in the absence of girth, a thong of hide passing around the horse's belly. The rider's dark features and keen snaky eye were unequivocally Indian. He wore a buckskin frock, which, like his fringed leggings, was well polished and blackened by grease and long service, and an old handkerchief was tied around his head. Resting on the saddle before him lay his rifle, a weapon in the use of which the Delawares are skillful, though, from its weight, the distant prairie Indians are too lazy to carry it.

"'Who's your chief?' he immediately inquired.

"Henry Chatillon pointed to us. The old Delaware fixed his eyes intently upon us for a moment, and then sententiously remarked, 'No good! Too young!' With this flattering comment he left us and rode after his people.

"This tribe, the Delawares, once the peaceful allies of William Penn, the tributaries of the conquering Iroquois, are now the most adventurous and dreaded warriors upon the prairies. They make war upon remote tribes, the very names of which were unknown to their fathers in their ancient seats in Pennsylvania, and they push these new quarrels with true Indian rancor, sending out their war parties as far as the Rocky mountains, and into the Mexican territories, Their neighbors and former confederates, the Shawnees, who are tolerable farmers, are in a prosperous condition; but the Delawares dwindle every year, from the number of men lost in their warlike expeditions."

The Delawares, however, were not given alone to fighting and hunting, as after events disclosed. They were an intelligent people, and their dealings and associations with the whites during the years of their migrations enabled them to acquire ideas of civilization. Like others of the emigrant tribes from the east a large number had embraced the Christian religion. Not a few of the men were Free Masons. If they were brave warriors and good hunters when first they came to Kansas, they were industrious. Through the influence of the early Christian missionaries, the traders and the white settlers they, in time, became good farmers, and they had much to do with the development of agriculture and fruit culture in Wyandotte county.

Major John G. Pratt, the Baptist missionary, was appointed by President Lincoln as agent for the Delawares. He was their trusted friend and counselor. One of his sons married a daughter of Charles Johnnycake, one of the Delaware chiefs. Writing for Andreas' History of Kansas, Major Pratt presents the following interesting account of the Delawares' sojourn of thirty-eight years in Kansas: "That part of Wyandotte county on the north side of the Kansas river was first settled by the Delawares in 1829. They came from Ohio and brought with them a knowledge of agriculture, and many of them habits of industry. They opened farms, built houses and cut roads along the ridges and divides; erected a frame church at what is now the village of White Church. The population of the Delaware tribe when it first settled in Kansas was about 1,000. It was afterwards reduced to 800. This was in consequence of contact with the wilder tribes, who were as hostile to the short-haired Indians as they were to the whites. Still the Delawares would venture out hunting buffalo and beaver, to be inevitably overcome and destroyed. Government finally forbade them leaving the reservation. The effect of this order was soon apparent in the steady increase of the tribe, so that when they removed, in 1867, they numbered 1,160.

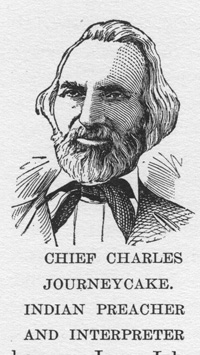

Among the ruling chiefs of the Delawares while they were in Wyandotte county, were Captain John Ketchum, Captain Anderson, Charles Johnnycake, James Secondine, James Connor and Captain John Connor

CHIEF CHARLES JOURNEYCAKE. INDIAN PREACHER AND INTERPRETER |

A pathetic incident of the Indian history of Wyandotte county was the death in August, 1857, of Captain John Ketchum, one of the most noted and best loved chiefs of the Delawares. It occurred only a few years before the departure of the Delawares from Kansas to the Indian Territory. The funeral was held at White Church, Wyandotte county, and the old settlers speak of it with reverence. A great sorrow befell the Indians and the whites as well, for not only was Captain Ketchum a good and kind chief, but he was also a preacher and spiritual adviser, a wise counsellor. The Indians came in their colored blankets, with painted faces, carrying their guns and mounted on their horses and ponies. As the procession slowly followed the body of the dead chief over the winding forest road to the burial place they seemed truly sorrowful survivors of a once mighty tribe.

In singular contrast from the spectacular funeral in July, 1857, of the great Delaware chief, was a simple service at White Church in January, 1911, for Mrs. Melinda Wilcoxen. Though of royal blood, a grandniece of Chief Ketchum, no brave warriors were there in paint and feathers and colored blankets to follow on their ponies the body as it was borne along the same road to the same old Indian burial ground not far from the site of the now vanished village of Secondine. Fifty-four years had wrought many changes, but not changed sorrow.

Mrs. Wilcoxen was born on the Wyandotte county reservation in 1830, the year after the Delawares came to Kansas, and was nearly eighty-one years old. When the Delawares departed from Kansas in 1867 she was left behind. She was the wife of Rezin Wilcoxen, a white man, and clearly she saw that her duty was to remain with her husband. A few persons of Delaware Indian blood are yet living in Wyandotte county, but in the death of Mrs. Wilcoxen the last full blood is gone. Hers was one of the beautiful love romances of her people and her presence in White Church through all these years, kept alive the tales of folklore of the Delawares. And this is the story she told a little more than one year before she died; while she sat in her substantial old fashioned home on the Parallel road at White Church:

"I was born a few miles south of White Church, some time in 1830. I never knew the month or the day. My mother's name was Aquam-da-ge-ockwe. My father was killed during a hunt two months before my birth. When I was about ten years old the government agents started me in a school near where Stony Point now is. Father Stateler was the teacher, but I did not learn much English. In 1851 I was married to Rezin Wilcoxsen, a West Virginian, who ran a store for the American Fur Company at Secondine, now called Muncie, Kansas. The Delawares were very much opposed to intermarrying with the whites, but my aunt and two of my cousins had married white men and my mother couldn't object much. The chief of the tribe, Captain Ketchum, was a brother of my grandmother, Eche-lango-na-ockwe. His Indian name was Tah-lee-a-ockwe, and signified to 'grab them' or 'catch them' and the whites called him 'Ketchum.' I had no brothers or sisters, but had six half brothers, and three half sisters.

"I was happy with my white husband until a year or two after we were married, when the government moved the Delawares to the Indian Territory. All of my friends and loved ones went away then, and I was sad and cried many days. I wanted to go too, but I had to stay with my husband. Finally, however, I became contented and my husband used to send me on frequent visits to my people in the territory. We owned a farm near Secondine, but when the survey of lands of the Wyandot Indians was made, in 1866, it was found that we were on their land, and we moved north and settled in our present home in 1867.

"We built our home in the early '80s, and here we raised our children. We had five children. My husband died in 1890, and now all of my children are married, or dead, and I am left alone."

While Mrs. Wilcoxen spoke English fluently, she constantly deplored the fact that no one is left who speaks her language. She did not teach her children Delaware, because she said she thought as all her people had moved away, they would have no use for it. For almost all of their lives Mrs. Wilcoxen and her cousin, Kate Grinter, a quarterblood Delaware Indian who died three years ago, attended the South Methodist church at White Church. The Sunday school children used to stand around in interested groups and listen to them converse in their beautiful Delaware tongue. But after Kate was gone Mrs. Wilcoxen had to croon to herself the accents of her 'dead' language. She used to go too into Kansas City, Kansas, to the home of Mrs. William Honeywell, a widow living at 1925 Hallock street, and talk with her in the Delaware tongue. But Mrs. Honeywell became deaf and could no longer converse.

"They are all gone," Mrs. Wilcoxen said, as she looked longingly at the setting sun. "I am sorry. I can say my thoughts so much better in my own Delaware, but maybe some day I'll see my baby again, and then we'll talk together of sunsets and rivers in our own language."

By a treaty with the Delawares, dated June 4, 1866, the secretary of the interior was authorized to sell what then remained unsold of the Delaware lands in Wyandotte county to the Missouri Railroad Company, at not less than two dollars and fifty cents per acre. Accordingly, by the terms of the treaty, in order to vest every holder of the real estate with a title from the government, all the lands were deeded in trust to Alexander Colwell, and he gave a deed to each Indian holding an allotment under the treaty of 1860. The lands then remaining unsold and unoccupied were sold at two and one-half dollars per acre to the railroad syndicate, consisting of Tom Scott, of Pennsylvania; Thomas Price, Len T. Smith, Alex Colwell, Oliver A. Hart and others, to the number of thirteen. These lands then came into the market, and the settlement that part of the county really began.

![]()

Transcribed from History of Wyandotte County Kansas and its people ed. and comp. by Perl W. Morgan. Chicago, The Lewis publishing company, 1911. 2 v. front., illus., plates, ports., fold. map. 28 cm. [Vol. 2 contains biographical data. Paged continuously.]