Map of Kansas showing the location of Barber County.

(18th Annual Report of the Kansas State Superintendent of Insurance, 1887, page 49.)l

From

The Principles of Judicial Proof

as Given by Logic, Psychology and General Experience, and Illustrated by Judicial Trials

Compiled by John Henry Wigmore

Professor of the Law of Evidence in Northwestern University

Boston. Little, Brown & Company, 1913.

(This web presentation includes photos and maps which were not part of the original publications.)

========== Page 856 ========== 856 PART III. PROBLEMS OF PROOF No. 389.

PRELIMINARY. ' The Hillmon the United States Circuit cases in Court for the District of Kansas are styled: Sallie E. Hillmon v. The Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York; Sallie E. Hillmon v. The New York Life Insurance Company of New York ; Sallie E. Hillmon v. The Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Company. These cases were docketed on the 13th of July, 1880.

The first trial was at Leavenworth, June 14 - July 1, 1882, before the Hon. CASSIUS G. FOSTER, of the United States District Court for the District of Kansas, the attorneys being L. B. Wheat, John Hutchings, R. J. Borgolthaus and S. A. Riggs for the plaintiff; and George J. Barker and James W. Green for the defendants. The jurors were as follows: R. B. McClure, Thomas White, James M. Walthal, Wm. Stocklebrand, E. H. Hutchings, Leonard Bradley, J. T. Fulton, Daniel Horville, Win. Lyons, J. S. Tood, John P. Gleich, and Samuel Kieser. This jury failed to agree, seven being for the plaintiff, and five for the defendants.

The second trial was at Leavenworth, in June, 1885, before the Hon. DAVID J. BREWER, United States Circuit Judge, the attorneys being L. B. Wheat, John Hutchings and Samuel A. Riggs for the plaintiff, and George J. Barlicr, J. W. Green and Charles S. Gleed for the defendants. The jurors were as follows: B. M. Tanner, J. P. G. Creamer, C. O. Knowles, H. D. Shepard, Nelson Giles, Jr., R. H. Stott, G. W. Greever, Wm. N. Nace, Joseph Kleinfield, Wm. H. Hamm, H. A. Cook, and P. B. Maxson. This jury failed to agree, Messrs. Tanner, Kleinfield, Stott, Maxson, Creamer, and Shepard being for the plaintiff, and Messrs. Greever, Giles, Knowles, Cook, Nace, and Hamm for the defendants.

The third trial was at Topeka, Feb. 29 - Mar. 20, 1888, before the Hon. O. P. SHIRAS, Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa, the attorneys being L. B. Wheat, John Hutchings and Samuel A. Riggs for the plaintiff, and George J. Barker, J. W. Green, Charles S. Gleed and William C. Spangler for the defendants. The jurors were as follows: Samuel Kozier, Jacob Moon, J. S. Bouton, A.S. Davidson, N.S. Miller, Riley Elkins, J.S. Earnest, John W. Farnsworth, Enoch Chase, Furman Baker, G.W. Coffin and J.P. Rood. This jury agreed on the second ballot, rendering a verdict of $35,730 (in all) for the plantiff.

The cases are now (April, 1888) in the Circuit Court pending the argument of a motion for a new trial. If this motion is overruled, an appeal will probably be taken to the United States Supreme Court.2

Footnotes to page 856:1. [A typewritten copy was supplied for use in this work, by the courtesy of Mr. Gleed. ' ED.]

2. [The appeal was so taken. In 1892 (Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. Hillmon, 145 U. S. 285). the judgment was set aside, and a new trial ordered. This fourth trial took place Jan. 9 - Mar. 19, 1895; the jury disagreed. The fifth trial took place Mar. 11 - Mar. 31, I896, and the jury disagreed. The sixth trial took place Oct. 17 - Nov. 18, 1899, and the jury gave a verdict for the plaintiff. This verdict was later affirmed on appeal : Connecticut Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Hillmon (107 Fed. 842, C. C. A., April. 1901); but was finally set aside in the Supreme Court (188 U. 8. 208, January, 1903), two judges dissenting. Of the three defendants, each had chosen a different course: The New York Life Insurance Co. had settled, in 1898, before the sixth trial, the case being dismissed. In 1896, during the Populist government, the State Insurance Commissioner had barred these three companies from doing business in Kansas, owing to the popular disapproval of the companies' resistance to the Hillmon claim. To regain admission to the State, this settlement was made. Later, upon a change of political administration, the bar was removed for all.

========== Page 857 ========== In stating the facts in this controversy, the writer has confined himself to the evidence adduced at the second and third trials, except as otherwise indicated; and, though sure that the companies are in the right, he still feels bound in this sketch to make a clear distinction between the facts and his construction of them ' between citations from the evidence, and his opinions. Aside from his knowledge of the cases as an attorney, he was one of the first newspaper reporters to become familiar with them, and has a personal acquaintance with most of the witnesses. Such familiarity gives him a knowledge of many facts which, under the rules of evidence, cannot go to the jury, but which might properly appear here. He has thought best, however, to avoid criticism by confining himself to what appeared or was closely suggested in court, and to further give both sides of the case a hearing by quoting the reports of the arguments made by the plaintiff's counsel at the trial at Leavenworth. These reports were made in the Daily Standard by Henry C. Burnett, now of New Mexico, also one of the first journalists engaged on the case, and a thoroughly competent and conscientious reporter. All citations from the testimony of the second trial are from the bound volumes of reports made by Mr. F. O. Popenoe, the official stenographic reporter. If the writer has made errors of any sort in quoting the evidence, they are certainly trivial and unimportant, as the utmost accuracy has been desired.

THE EVIDENCE. Hillmon and Wife, before Hillmon's Disappearance. (In Evidence.) ' John W. Hillmon was born in Indiana, in 1845, and was therefore about thirty-four years of age at the time of his alleged death near his father, who settled near Valley Falls, Jefferson county, Kansas. (See Hillmon family in 1860 census) He attended school more or less, and then became a cattle herder and farm laborer, working for various farmers and cattlemen in Jefferson, Leavenworth, and Douglas counties. He entered the army in 1863, at eighteen years of age, and remained about one year, In 1874 he went to Colorado, and worked in the mines at Quartzville and Central City as a miner and mining boss. In 1876 he returned to his home in Kansas, and resumed his occupation as cattle herder. He left Kansas again in 1876, going to Sweetwater and Reynoldsville, Texas, where he engaged in killing buffalo, gathering buffalo bones and hides, and in hauling freight. He returned to Kansas via New Mexico and Colorado, selling the ox teams of his Texas outfit at various points on the return trip, and arriving at Lawrence in August, 1877. For a time he bought and sold hogs in Lawrence. On or about December 15, 1878, he left Lawrence for a trip to Wichita, Dodge City, and other western and southwestern points, as he said, to find a cattle ranch, leaving Wichita December 26, 1878.

Map of Kansas showing the location of Barber County.

The following extracts from his pocket journal will show the character of this first trip, the journal or memorandum book having been taken from the body of the man killed near Footnote to page 857: The Mutual Life Insurance Co. of New York, in 1900, made satisfaction of the judgment obtained in 1899 on the sixth trial. The case was dismissed against the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Co., in 1903, presumably because of a settlement after the Supreme Court's order for a new trial. Thus ended the Hillmon Case. For most of this later history of the case, the Compiler is indebted to Morton Albaugh, Esq., Clerk of the United States District Court for the District of Kansas, at Topeka. ' Ed.

========== Page 858 ==========

"John W. Hillmon's book; residence, Lawrence, Kansas. Mrs. S. E. Hillmon, corner Henry and Alabama streets, Lawrence, Kansas. Traveling companion, J. H. Brown; residence, Wyandotte, Kansas.On January 25, 1879, Hillmon went from Wichita to Lawrence, for a few days, and returned to Wichita, leaving there on March 4, 1879, on his next and last trip, prior to his disappearance at Crooked Creek, a"My first memorandum I lost after I had been out a few days, so I replaced it with a new one. Could not recall all that I had in my first, but placed my dates correct. I lost it the second day from Wichita, together with some cough medicine; I had caught a severe cold at Wichita, and provided for it. Colds are numerous through this part. Prescription, Bon Bay root.

"December 18th. I left Lawrence on the 18th of December, 1878, for the purpose of looking up a stock ranch in the southwest. Went by way of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe to Wichita. Arrived at Wichita at twelve at night. Found snow about three inches deep.

"December 19. On the morning of the 19th looked around town during the day. Wichita is a livery town. Streets full of teams every day. They will face the storm to go to the city.

"December 20. Rather warm overhead. The snow melting some. Wrote a letter home, and one to Baldwin. Looked around some for a team. Did not get any up to this evening.

"December 26. Started early for the west. Turned cold and began to storm. Drove all day, nearly facing the storm. The country is dotted with houses all over the prairie. No timber and no accommodations to amount to anything. Stopped at night about 25 miles from Wichita. Their principal fuel is corn stalks.

"December 27. Cold. A long drive through rather an unsettled country. Jack frosted his feet. Had to break road most of the way. Horses as well as us was very tired. Stopped for the night with some Hoosiers, though they made us very comfortable.

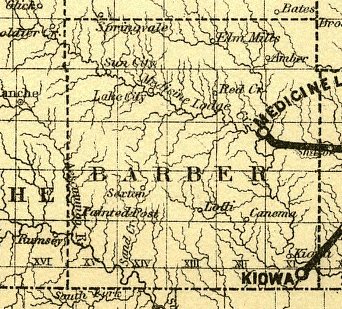

"December 28. Drove thirty-five miles, and arrived at Medicine Lodge affords a very good congregation for a new and frontier town.

"January 6. After looking around we find that we have broke our wagon. Will have to go back to Sun City to get it fixed. The wind is blowing very hard and cold. I think something very strange will happen soon. It has not snowed any since yesterday. Have just had a good time after our horses. They got loose and ran all over the country. Think they are done running for a while except they are hitched up. Last night was very cold and blustery. This morning, the 7th, threatened snow. Wind cold from the north. We are in camp on the Medicine river, at Myers's ranch, about twelve miles west of Sun City. Jack is complaining with cold. Nothing to do to-day except set by the fire, and it smokes so we can hardly see at times. This kind of weather will make one almost curse camp life, and himself for being so silly as to start on a trip of this kind during the winter months I have prophesied a cold winter this winter, but so far it has overreached my expectations. My opinion was formed by the extra quality of all kinds of furs, both small and large. Muskrats in the north build higher than they was known to for years. The sun goes down tonight dark with snow and wind. I think it has been as blustery an afternoon as 1 have ever witnessed. This kind of weather is what will condemn this part of the country for stock. It will be almost impossible to save near all of the stock. Admitting it a good country, why was man made to drift in the world like wild animals? I guess the intent was good, and our life what we make them. I would freely give fifty dollars if I had postponed my trip until one month later at least. I think then a man would have some show to travel

========== Page 859 ========== with safety, while now he has but very little.

"January 8. Rather pleasant overhead. Old man Myers came down to camp and talked until we both had the headache. He thinks himself the pioneer of Kansas, and has only been in the country about four years. He says woman is a swindle, and that every one knows. At least his, for they look worse than h__l sewed for murder. We have concluded that we will set in camp a day or two longer, and see what the weather is going to do. A fair prospect for a good day to-morrow.

"January 12. We left Medicine river early in the morning. It had every appearance of being a beautiful day. Traveled northwest. Crossed the head of Spring creek, near Bannister's ranch. We found the road very rough and tiresome. The sand hills numerous. Snow badly drifted in many places. We put up for the night at Smith's ranch, 14 miles southeast of Kinsley. I should like to own all this country, if I had it on a big hill or mountain where I could roll it down by sections. I think then I could save many from living out a miserable existence, which they are trying to do here on these bald prairies, without wood or coal to keep themselves warm. If the country affords such, many of them are not able to buy, but burn corn stalks and hay.

"January 20. Warm and pleasant overhead. Roads very bad. Mud and ice. Arrived in Wichita in the afternoon. Think we will wait a few days and see if the traveling will get better. Think will go south to the Nation line next time.

"January 22. At Wichita waiting for the roads to get a little better. They are very muddy. The weather looks some like a storm again, cloudy and dark. Wichita is packed with teams in the streets. I think it is the boss town of Kansas for business. Hogs seem to be in good demand. Buyers are quarreling over them to-day. They are bringing $2.60 for good ones. Wheat 54 cents. Corn is selling at about 18 cents. Wichita is having a glorious time, that is, the praying portion of the city. 22d. Went to church in the evening. Thought it would last all night. They have several mourners ' fish for the preachers.

"January 25. Started home morning at 5 o'clock. Arrived at Lawrence half- past three evening. Met Mr. Wiseman of the Mutual Life, Topeka.

"January 26th and 27th at home.

"January 28. Left Lawrence 12.40 by A. T. & S. F. for Wichita. Weather damp and cloudy. Arrived at Wichita at 10 in the evening.

"February 8. Still I remain in Wichita waiting for the roads to get in a passable condition. They are very bad. I think I have never did as hard work in my life as I have done in the past six weeks. It is killing me almost by inches to loaf around and do nothing as I have been doing of late. I think I will leave here within a day or two, if I have to go home.

"Monday, 17th. Cloudy and cool. Am at home in Lawrence.

"18th, 19th and 20th, at home.

"23d. Came home in the evening. Very warm. Don't see as there is any good to grow out of me trying to keep track of my misdeeds, while I am apt to err as any one. And that I would be sure ashamed not to make a memorandum of, and only show up the best parts as others have done before me. I do not want to be an exception to the rule or make any new ones so to keep from answering any hard questions. If any one should want to know where I spent my evenings I will say to them I have forgotten to make a memorandum of the time, and my memory is bad, as I never charge it with anything, and of course cannot answer prompting. So ends this part at Lawrence.

"February 23, 1879.

"(Signed) J. W. HILLMON."

========== Page 860 ========== few miles from View marriage license) Hillmon and wife lived in one room in the house of Mrs. Judson, where they were married, in Lawrence. Mrs. Hillmon was a second cousin to Levi Baldwin, who lived near Tonganoxie, Leavenworth county, Kansas, and who was Hillmon's best friend. Mrs. Hillmon came to Kansas from Columbus, Ohio, at an early age, and had been employed at Lawrence as a family servant, and waiter in a restaurant, which was managed by her mother.

Hillmon was always a poor man. No one knows of his ever having had money or property of consequence except the train taken from Texas and sold in Mexico and Colorado (his possession of which is explained later), and two notes given to Hillmon by Levi Baldwin, and produced for the first time on the last trial. Three notes, signed "Hillmon & Brown," the signatures having been identified as the work of Hillmon, and the notes having been executed to McKamy & Anderson, of Texas, were introduced by the defendants to contradict the evidence that Hillmon had money above his debts. The Texas parties, to whom these notes were given, wrote to the City Marshal of Lawrence, saying that Hillmon was wanted. Hon. J. B. Johnson holds an unpaid note of Hillmon's for $100, given by Hillmon for professional services, which note has never been collectible.

An accurate description of Hillmon at the time he was last in Lawrence, is as follows: Weight, 165 pounds; height, 5 feet 9 inches; hair, brown; mustache, full; teeth, imperfect, and one gone; face egg-shaped, and broadest through the temples; cheek bones, medium, and not prominent or high; nose, straight and regular; jaws, tapering to the front; lips, closed; scar on back of head and on hand, and vaccination sore on arm.

(Not in Evidence.)' Hillmon and Brown bought the train which they used in Texas of McKamy and Anderson, and gave back the three notes for about $1600 each above referred to, and a bill of sale for the train. The train was taken to New Mexico and Colorado and sold as also above stated, and the notes were never paid. It was on this account that the police inquiry came from Texas to City Marshal Brock- elsby, of Lawrence. Hon. W.N. Allen once paid a bond for about $100 for Hillmon when the latter had been arrested in Jefferson county, with others, for brutally trying to force information out of an old farmer on the subject of horse stealing.

(Comment.) ' From all the evidence it appears that Hillmon was a rough character, familiar chiefly with the hard life of the soldier, the plainsman, the miner, the hunter, and the cowboy; accustomed to seeing human life held cheaply; practically an outlaw; absolutely poor; without a definite occupation; with no particular respect for women, or home, or relations, or law. He was mentally active, however, and always had work or business of some kind in which he showed more or less cunning and shrewdness. His penmanship was better than ordinary, and his journal gives evidence of considerable crude thought. Such was John W. Hillmon at the time of his disappearance.

From all the evidence it seems that Mrs. Hillmon before marriage was a young woman of good character and industrious habits. As a family servant and waitress in a

========== Page 861 ========== restaurant she supported herself, and perhaps assisted in the support of her mother and sister, her father being dead. Her marriage does not seem to have materially changed the situation, as her subsequent living arrangements were of the simplest sort. After the insurance quarrel began, she entered on the interesting chapter of her life. In nine years she has traveled much and prospered fairly. She may or may not be married. She was not asked her name by any of the attorneys, but she was accompanied through the trial by a Mr. Smith, who is understood to be her present husband. Why her attorneys did not develop this fact, if fact it be, on the trial, the writer does not know.

The Insurance Transaction. (In Evidence.)'Shortly after the marriage of Hillmon, which took place October 3, 1878, he went with his friend Levi Baldwin to the office of J. H. Blythe, attorney, at Tonganoxie, a small town in Leavenworth county, and asked his advice as to the best methods for securing insurance. Mr. Blythe was not a regular insurance agent, but he told Hillmon and Baldwin what he knew in the line of their inquiries. On the 31st of October, 1878, Hillmon and Baldwin went to the office of A.L. Selig, a well-known insurance man in Lawrence, to whom Hillmon applied for insurance in the New York Life Insurance Company in the sum of $5000. On December 4, 1878, he and Baldwin again called on Mr. Selig and applied for a second policy on the life of Hillmon in the New York Life Insurance Company in the sum of $5000. The New York Life Insurance Company issued policies on the applications made to it. The Connecticut Mutual was refused on technical grounds. On the 4th day of December, the same day the applications were made, Hillmon and Baldwin called also on G. W. K. Griffith, of Lawrence, and made application for insurance in the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York in the sum of $10,000. The Mutual Life Insurance Company issued a policy as applied for. On February 14, 1879, Hillmon returned from Wichita to Lawrence, and applied for a policy in the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Company in the sum of $5000, which policy was granted. This gave Hillmon insurance for $10,000 in the Mutual Life of New York, $10,000 in the New York Life, and $5000 in the Connecticut Mutual, the total being $25,000 in all. The annual premiums on this sum called for about $60 a month. Hillmon made the first semiannual payments, part in cash, and part by one note, the latter being given to Mr. Selig, agent of the Connecticut Mutual Company.

The insurance agents testified that they had never known of Hillmon's personal character or financial standing when the policies were issued, except that he was vouched for by Levi Baldwin as a cattleman with money. Baldwin was a farmer, supposed to be in good circumstances, but subsequent evidence proved that he was bankrupt. Mr. J.S. Crew, as assignee of a bank, had to foreclose a mortgage on Baldwin's farm. Baldwin asked him to wait until the money was paid on Hillmon's insurance, as he would then have $10,000. After the litigation commenced, Crew would wait no longer, and the foreclosure was made, after which Baldwin removed to New Mexico.

One policy was declined because Hillmon wanted permission to ride fast after cattle and carry firearms. Hillmon's last visit to Lawrence seems to have been on a matter of life insurance, as a question had been raised as to the validity of his policy, on the ground that he had never been vaccinated. He objected to vaccination until assured beyond a doubt by the agents of the company that in case of death, his policy would be void, on the ground of his...

(Pages 862 and 863 are not included in this transcription.)

========== Page 864 ========== ... they had seen in the wagon with Brown going west. The Col. Sam Walker, who saw the body when it was first exhumed at Medicine Lodge; A. L. Selig, Mr. Tillinghast, and G. W. E. Griffith, insurance agents; Edward Monroe, a hackman who had carried Hillmon; George Gould, an implement dealer; Joseph Bebout, a farmer ; Wm. Brown, another farmer (the three latter having done business with Hillmon; Wm. Brockelsby, City Marshal of Lawrence, who at the time of the disappearance was looking for Hillmon on information from the Texas parties who had lost their teams; Frank L. Wroodruff, merchant, who had traded with Hillmon frequently; Dr. V.G. Miller, who examined Hillmon for his policy in the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, and who knew him well; Dr. J. H. Stuart, who examined Hillmon for his policies in the New York Life, and who vaccinated him on the 20th of February; and Dr. C. V. Mottram, who also knew him. Dr. Stuart met Hillmon in Selig's office October 31, 1878, and on that day examined him for life insurance. Early in December he examined him again for another policy. On the 20th day of February he vaccinated Hillmon at two points on the left arm. Hillmon consulted him five or six times about the vaccination. All or practically all of the witnesses above named as having sworn positively that the body was not that of Hillmon, based their belief, first, on their general inability to recognize the dead face; and. second, on the facts that the dead man, as compared with Hillmon. had very much darker hair, higher cheek bones, a broader chin, a more Roman nose, larger hands and longer arms, better teeth, larger

========== Page 865 ========== feet, and a longer measurement. Not all of these witnesses testified to all of these facts, but all testified to some of them, and nearly all to nearly all of them.

An important branch of the testimony of identification was the tooth testimony. The following-named witnesses, thirty-eight in number, testified that Hillmon had a defective tooth, or was minus a tooth altogether from the front part of the upper jaw, most of them locating it on the upper left side, immediately in front of the eyetooth; Major Wiseman, Colonel Sam Walker, Oliver Walker, William Hogan, Jackson Hogan, Tinnette Korkadel, Charles Snow, Josiah B. Brown, James T. Cameron, Mrs. M.J. Dart, Dr. V.G. Miller, Frank H. Hatch, J.E. Taylor, W.S. Angel, H.D. Marshall, Mrs. Win. T. Faxon, Joseph Bebout, Claude Holliday, Harriet Adams, James A. Adams, E.L. Emmons, Mr. Rothwell, R.A. Brown, Joshua Wilson, William Brockelsby, Mrs. Smith, Win. T. Faxon, Mary Carr, Margaret Jane Kaufman, Jackson Taylor, Robert Blake, S.D. Nixon, Mrs. Harris, W. W. Nichols, George A. Nichols, Mrs. Geo. A. Nichols, Maggie J. Dixon, and Jefferson Schleppy . Wiseman remembered that there was something imperfect about Hillmon's front teeth. Colonel Walker remembered that once when lying on a bunk in his stable, Hillmon came to the place where he was lying, and hung his overcoat on a nail over him. While they were in this relative position, Walker noticed the absence of one tooth in the front part of Hillmon's upper jaw, and remembered it at the time because his son Oliver has lost a tooth in exactly the same place. Oliver Walker remembered the same circumstance ' the absence of the tooth ' because of having himself lost a tooth from the same place. Wm. Hogan remembered a defective tooth. Tinnette Korkadel, of Valley Falls, was a schoolmate of Hillmon's, and for many years an intimate friend of the family. She remembered that as a boy Hillmon had a black or discolored tooth on the left front of the upper jaw. Hillmon was once very attentive to her. James T. Cameron knew Hillmon when both were farmers in the same neighborhood. They once had a conversation with reference to the missing tooth. Cameron swore positively that the tooth next to the upper left-hand eyetooth was gone. Mrs. M.J. Dart, who had seen Hillmon and Mrs. Hillmon at her house, swore positively as to the missing tooth. Mrs. Faxon was at the house of Wm. T. Faxon, whom she subsequently married, when the first Mrs. Faxon was ill. Sallie E. Quinn was a domestic in the employ of Mrs. Faxon at that time. One day she received a call from Mr. Hillmon, and Sallie asked Mrs. Faxon what she thought of her choice. Mrs. Faxon replied that she liked him much, but that it was a pity that he had lost a front tooth. Wm. T. Faxon on that occasion noticed the absence of the tooth, and as he had been buying false teeth for his wife, made some remark as to how much it would cost to put a false tooth in Hillmon's mouth. This remark caused his wife some annoyance, as she considered what was said as a complaint about the expense which she had thus incurred. Mr. and Mrs. Faxon swore positively as to the missing tooth. Josiah Wilson knew Hillmon near Tonganoxie. He swore positively that Hillmon had a tooth out of the left front of the upper jaw. Claude Holliday knew Hillmon intimately, and remembered the absence of the tooth. He mentioned one time in particular when the absence was more than usually noticeable, because Hillmon laughed. George A. Nichols and his wife, Hillmon's sister, formerly Mary E. Hillmon, both testified positively to the absence of a tooth from their brother's upper jaw on the left side, front. Mr. Nichols

========== Page 866 ========== had known Hillmon since 1865, and had been his most intimate friend. He first noticed the entire absence of a tooth in 1872, but before that had noticed for many years that a tooth was discolored. W.W. Nichols, brother of G.A. Nichols, knew Hillmon intimately, and swore that one of his upper front teeth was either out or defective. Dr. Miller, in making his examination of Hillmon for insurance, noticed the absence of a tooth from the left front of the upper jaw. Jefferson Schleppy, cousin to Hillmon, testified to the absence of the tooth.

(Not in Evidence.) ' Dr. Howe, a Lawrence dentist, now living in the City of Mexico, says that some time before the Hillmon affair became notorious, two men called upon him to have an artificial tooth made for the position in front and next to the eyetooth, on the left side of the upper jaw. He did not know Hillmon, but identified Brown as the other of the two men. His books were destroyed, so that any entries which he might have made could not assist him in identifying the men. The plate was never called for, and Mr. Howe lost what he had in the job.

(Comment.) ' The cross-examination of all these witnesses elicited the fact that there were many persons with whom they were intimately acquainted, the condition of whose teeth they could not tell. They were asked about the merchants with whom they dealt and other people with whom they were well acquainted, various questions as to teeth, etc., the majority of which questions they were unable to answer as definitely as they were swearing on the subject of Hillmon's lost tooth.

(In Evidence.) ' A small item in the testimony of identification related to the hair. One of the Walters sisters testified in a general way that her brother's temples were bare. A witness for the plaintiff swore from the looks of the pictures that the hair of the dead man grew over the temples. Hillmon's hair was an ordinary brown. Walters had hair almost black; so had the corpse. The testimony as to the quality of Walters' hair and Hillmon's was mixed, some saying one way and some another ' the difficulty evidently being that no two witnesses had the same standard of comparison.

Another item of importance was the fact that the clothes of the dead man were slightly too small for him. This was observed by the members of the coroner's jury, the undertakers, and the physicians.

Another important branch of the testimony of identification was the vaccination testimony. Dr. Stuart vaccinated Hillmon on the 20th of February, and on the 25th the vaccination was found to be "working" well. The dead man was killed on the 17th of the following March, 27 days from the date of the vaccination. The vaccination scabs on the dead man's arm were found to adhere closely to the arm, and had to be removed, if at all, with force. The area of the vaccination was cut out by Dr. Stuart from the arm of the dead man and preserved in alcohol. It was of no possible use to anybody, and so was thrown away when Dr. Stuart removed from Lawrence. The defendant maintained and the physicians testified that the course of a healthy vaccination would have left the arm practically well in a period of twenty-seven days. As the vaccination scabs showed the vaccination to be a perfectly healthy one, so far as could be determined by careful examination, the physicians for the defendants, Drs. Miller, Mottram, Morse, Stuart, Branstrup, Alexander, Jones, and Hibben, gave it as their opinion that the vaccination marks on the dead body could not have been from the vaccination of Hillmon done on the 20th day of February. All these physicians, as

========== Page 867 ========== well as several called by the plaintiff, testified that an unhealthy condition of the body or an accident might have prolonged the life, so to speak, of the vaccine sore, and it was this remote general possibility which was relied on to nullify the defendants' testimony on this subject.

(Comment.) ' The physicians were practically a unit on the subject of vaccination. All maintained that the progress of a perfectly healthful and uninjured vaccination sore was definite and certain ; that an injury, like a blow, or any gross impurity of the blood, would prolong the sore; and that any sore so prolonged would have a different appearance from the perfectly natural vaccine sore. The sore on the dead man was a perfect vaccine sore, as sworn to by the four physicians who saw it.

(In Evidence.) ' Another important branch of the testimony of identification was that in relation to the condition and contents of the stomach of the dead man. Brown and Hillmon, according to the testimony of the former, had eaten a meal of bacon, bread, and coffee about an hour before sundown on the afternoon of the killing. The physicians, testifying for the defendants as above named, gave it as their opinion that the occurrence of death at the length of time mentioned after eating, in cold weather, would cause evidences of undigested fowl to be found in the stomach. The post-mortem examination only revealed a small quantity of mucus. The physicians agreed that digestion under some circumstances could go on after death ' that is, given food and gastric juice in a stomach not too cold, a chemical action would take place which would result in the dissolution of the food. Such action would take place in any receptacle as well as in the stomach. The greatest range of temperature given as permitting this chemical action was between zero and boiling point, Fahrenheit. It was also shown that if the food in the stomach of the dead body had become decomposed ' particularly if it had become decayed and gaseous ' the rough riding from

========== Page 868 ========== of Selig, and made a memorandum on a blank leaf of his office ledger as to the result of that measurement, which was five feet nine inches. The memorandum in the ledger was written out in full, dated, and sworn to as having been made at the time of the measurement, and as accurately recording the results of that measurement. The memorandum itself was not admitted as evidence, but the Doctor was permitted to hold it in his hand, and from it refresh his memory as he testified. Mr. Selig was present when this measurement was made, and knew all about it, excepting that he could not swear that he actually examined the measuring-line himself as it was applied to the wall. The memorandum made was as follows:

"Lawrence, Kansas, December 17, 1878 ' John W. Hillmon called on me and reported a slight mistake in his height. He, Hillmon, is five feet nine inches, in place of five feet eleven inches, as stated in his policy for life insurance in the New York Mutual.

"V. G. MILLER."Hillmon also stated the correction as to height to Dr. Stuart, but no memorandum was made of it. The witnesses as to Hillmon's height ' to the effect that he was five feet nine inches high ' were J.H. Stuart, Dr. V.G. Miller, Major Theo. Wiseman, Joseph Helmut, A.L. Selig, W.W. Nichols, Geo. A. Nichols, Mrs. Nichols, Draves of Wichita, H.D. Marshall, Claude Holliday.

Another important branch of the testimony of identification related to the scar on Hillmon's hand. W.W. Nichols swore that once when he was in camp with Hillmon in Texas, and while some general shooting was being done at a mark, Hillmon attempted to crowd a loaded cartridge into his breech-loading gun with a stick, and exploded the cartridge, the shell of it cutting a long wound around the base of one thumb, and an inch, more or less, on the outside. This wound left a scar, which was sworn to as being very plainly seen subsequently by W.W. Nichols, G.A. Nichols, and Mrs. G.A. Nichols, Hillmon's sister, when Hillmon was making his sister's family a visit, in Washington county. H.D. Marshall and Rufus Whitney also swore to the scar.

William Brown traded shoes with Hillmon, and George A. Nichols and Jefferson Schleppy also testified as to the size of Hillmon's foot. It was a foot calling for shoes number eight or nine. The dead man's shoes mysteriously disappeared on the trip between

========== Page 869 ========== Medicine Lodge; thence to Sun City; thence to a

========== Page 870 ========== town on the Santa Fe road; thence to Great Bend; thence to Hutchin- son; thence back to Wichita. Between the return to Wichita and the departure for the second trip Brown testified that Hillmon returned to Lawrence.

On the second trip the two men went from Wichita to Kingman; thence to Harper City; thence to Sun City; thence to Elm creek, finally to Crooked Creek, where the disappearance took place. Brown testified that he arrived at Crooked creek on the 16th of March, and that while in camp during the next day a man called during the forenoon. In the afternoon Brown and Hillmon had been shooting with a gun at a mark, and after they were through Hillmon put the gun back in the wagon, with the muzzle sticking out. About bedtime Brown went to get ready for bed. He took hold of the barrel of the gun and pulled it over his right shoulder. The hammer caught on the wagon, and the gun was discharged. Brown testified that he dropped the gun, turned, and went to Hillmon, who was twelve feet distant, and caught him before he fell, and swung him around away from the fire. He then got a horse and went three quarters of a mile to a house and told what had occurred. The man of the house returned with him to the camp. The man's name was P.B. Briley. He was the same man who was at the camp in the morning.The next morning Esquire Paddock held an inquest. They then took the body and went to Medicine Lodge. After Levi and Alva Baldwin, Colonel Walker, Major Wiseman, and Tillinghast came from Lawrence, Brown went to the grave to help take up the body. He returned with the body to Lawrence. Brown testified that when they left Wichita on the last trip a man stayed with them all the time they were at Cowskin creek. This man joined them about three miles out from Wichita. The stranger left, and was not with the two men at camp when the disappearance took place. When the inquest was held at Lawrence, Brown, after giving his testimony, left town in a hurry, and returned to the vicinity of Wyandotte, where Brown's father lived. Brown's father applied to State Senator W. J. Buchan, at Wyandotte, for help for his son. This was in March, 1879. The elder Brown explained the difficulty in which John had become involved, and asked Buchan to go to Lawrence and try to manage the matter. This Buchan did, without result. Some time later, Reuben Brown, brother of John Brown, called on Senator Buchan, and asked him to go to Lexington to see John. At Lexington Buchan and Brown discussed the matter fully, and Brown stated that the job was as bad as it could be, and he wanted Buchan to see the agents of the insurance companies, as he, Brown, wished to turn State's evidence and get out of the difficulty. Brown went across the street from the railroad track and wrote the following letter:

"Mirs Hillmon i would like to now where Johny is and How that business is and what i shall doe if anything. Let me now threw my Father.

"JOHN H. BROWN."Senator Buchan testified that this letter was written by Brown in order to get information out of Mrs. Hillmon about her husband. Buchan again saw Brown at Parkville, and found Levi Baldwin trying to get Brown to sign proofs of death. Baldwin told Brown that he would not have to go on the stand, as the theory of the insurance companies was that the body was that of Frank Nichols, and that was as good a thing as he (Baldwin) wanted, as he could produce Nichols in court. Buchan told Brown that he would be compelled to go and testify,

========== Page 871 ========== which he said he would not do. He again proposed to turn State's evidence, which fact Buchan had previously reported to the insurance companies.

On the 4th of September, 1879, Buchan went again to Parkville, and asked Brown to put his statements in writing. This Brown did, and afterward went before Justice McDonald and swore to the statement. This statement or confession was as follows:

"STATE OF MISSOURI, COUNTY OF PLATTE, ss.: John H. Brown, of lawful age, being first duly sworn according to law, deposes and says: My name is John H. Brown. My age is thirty years. I am acquainted with John W. Hillmon. Also Mrs. S. E. Hillmon, and Levi Baldwin, of Douglas County, Kansas. Have known John W. Hillmon for about five years. Have been with him a good deal for the past two years. Was with him last March at Wichita, and on the trip from there to and around Sun City; from there to Kinsley; from there to Great Bend, on the Santa Fe road; then to Larned, and on to Wichita via Hutchinson. Hillmon and myself were entirely alone on this trip. Iliff, of Medicine Lodge, on by Sun City, and beyond some miles. Then we turned northeast down Medicine river to a camp on Elm creek, about eighteen miles north of"Brown gave Buchan a power of attorney to act for him in securing immunity from prosecution, in return for his confession. Subsequently Buchan also had from the insurance companies the same sort of power of attorney to bind them to what Brown required. These authorizations were as follows:========== Page 872 ========== one and then the other would be kept back out of sight. On his trip up to Lawrence, Hillmon was vaccinated. His arm was quite bad. Hillmon kept at the man until he let him vaccinate him, which he did. taking his pocket-knife and using virus from his own arm for the purpose. He also traded clothes with him, Hillmon first giving him a change of underclothing, then trading suits ' the one he was killed in. The suit he was buried in was a suit Hillmon traded with Baldwin for. This man appeared to be a stranger in the country, a sort of an easy-go-long fellow, not suspicious or very attentive to anything. His arm became very sore, and he got quite stupid and dull. He said his name was either Berkley or Burgess, or something sounding like that. We always called him Joe. He said he had been around Fort Scott awhile, and also had worked about Wellington or Arkansas City. I do not know where he was from, nor where his home or friends were. I did not see him at Wichita that I know of. I had but very little to say to the man, and less to do with him. He was taken in charge by Hillmon, and yielded willingly to his will. I dreaded what I thought was to be done, and kept out of having any more to do with him than possible. I frequently remonstrated with Hillmon, and tried to deter him from carrying out his intentions of killing the man.

"The next evening after we got to the camp last named, the man Joe was sitting by the fire. I was at the hind end of the wagon, either putting feed in the box for the horses or taking a sack of corn out, when I heard a gun go off. I looked around, and saw the man was shot, and Hillmon was pulling him away around to keep him out of the fire. Hillmon changed a daybook from his own coat to Joe's, and said to me everything was all right, and that I need not be afraid, but it would be all right. He told me to get a pony, and go down to a ranch about three quarters of a mile, and get some one to come up. He took Joe's valise, and started north. This was about sundown. We had no arrangements about communicating with each other. He first promised to do so, but I told him I did not want to know where he was; that in case I should, I might find out some other way. I have never heard a word from him since. At Lawrence, Mrs. Hillmon gave me to understand that she knew where Hillmon was, and that he was all right. The man over whom an inquest was held at camp, afterwards at (Signed) JOHN H. BROWN.

Subscribed in my presence, and sworn to before me, this 4th day of September, A.D., 1879. My term expires on the 2d day of April, 1883.

(Seal.)

FRANCIS M. MCDONALD, Notary Public.

========== Page 873 ========== "PARKVILLE, Mo., Sept. 4, 1879.

"I hereby authorize W. J. Buchan to make arrangements, if he can, with the insurance companies for a settlement of the Hillmon case, by them stopping all pursuit and prosecution of myself and John W. Hillmon, if suit for money is stopped and policies surrendered to companies.

"JOHN H. BROWN.""W. J. BUCHAN, ESQ. ' Dear Sir: On behalf of the Mutual Life the New York Life, and the Connecticut Mutual Life, I hereby authorize and employ you to procure and surrender the policies of insurance on the life of John W. Hillmon.

" H.B. MUNN.

"KANSAS CITY, Sept. 5, 1879."The transaction, so far as Buchan was concerned, became an arbitration, with himself as arbitrator. Brown then authorized Buchan to say that he would testify in accordance with his statement or confession, provided the companies would take no steps to prosecute Hillmon, Mrs. Hillmon, Baldwin, or himself. The insurance companies, on the other hand, were bound to do what Brown required of them according to the terms of his proposition. Senator Buchan said that after the papers were signed he returned home, and next saw Brown at his office in Wyandotte. At the time of signing the statements Brown spoke of getting Mrs. Hillmon to surrender the policies. Buchan told him that if he did that, it would probably end the matter. He said he would see Mrs. Hillmon. Buchan promised Brown not to show his statements to the authorities or to reveal his whereabouts until he, Buchan, had secured their promise not to prosecute, as above described. Brown went to see Mrs. Hillmon at Levi Baldwin's house. Baldwin went to Lawrence on horseback and brought Mrs. Hillmon out by getting a neighbor to carry her part way, as the roads were bad, and taking her the rest of the way himself. At about eleven o'clock at night Mrs. Hillmon and Brown met at Baldwin's house, and, according to Mrs. Hillmon's testimony, Brown told her that he had turned State's evidence, and could not testify for her in the insurance cases. The next morning they had another interview, and made an appointment to meet at Leavenworth on September l5th, 1879. Brown, Mrs. Hillmon, and Buchan met at Leavenworth. The policies were with Mr. Wheat, at Leavenworth. Mrs. Hillmon signed full release of all her interest in the insurance policies. She also went with Buchan to Mr. Wheat's office to demand the policies. Mr. Wheat refused to give up the policies, saying be had a lien on them for $10,000. Mrs. Hillmon and Buchan returned to Wyandotte. Buchan showed Mrs. Hillmon the agreement of the companies not to prosecute Brown. Also Brown's statement. This statement was torn up and put in the stove, but was afterwards fished out of the stove and preserved, when it developed that there was to be a contest over the policies. Mrs. Hillmon remained in Wyandotte some time with Buchan. She afterwards went to Ottawa. Returning from Ottawa she signed a supplementary release, and afterwards stayed for about three weeks at Buchan's house. She went to Trenton, Missouri, where she stayed three weeks or a month. Buchan had nothing to do with fixing the place of meeting at Leavenworth, he going there at Brown's request. Buchan got no fees from the Browns, but did get from $500 to $700 from the insurance companies, including expenses. Mr. Wheat was retained by Levi Baldwin.

While absent from Wyandotte, Mrs. Hillmon wrote to Buchan the following letter:

"Saturday Jan. the 3, 1880

"HON. W. J. BUCHAN, WYANDOTTE : I am now ready to go to Colorado as soon as you send the ticket and money. I hope

========== Page 874 ==========

========== Page 875 ========== (Pages 874 and 875 are missing from this web page.)

========== Page 876 ========== rado, and parts unknown to me. I expect to see the country now. I will close. Regards to all inquiring friends; love to all. "Your brother,

"F. A. WALTERS."At the same time Mr. C.F. Walters, the brother at Holden, Missouri, received a letter from him, stating that he was about to leave Wichita with a man by the name of Hillmon. Since that time, no word has ever been received by the friends or family of Walters, nor has any person with whom he was before acquainted seen him.

Some time after this, his people became alarmed by his continued silence, and began to make inquiry. His father applied to the Odd Fellows' Lodge at Fort Madison, of which his son was a member, but it did nothing for him. He then applied to the Masonic Lodge for assistance. Mr. Hobbs, a bright young lawyer of that place, was the master of this lodge. He at once applied to the lodge at Wichita for assistance. The lodge at Wichita wrote to Lawrence, and in response, pictures of the dead body which had been brought there were forwarded to it. These pictures in turn were forwarded to Mr. Hobbs, and by him shown to the father, who immediately recognized them as pictures of his son, Frederick Adolph Walters. He showed them to the members of the family, and one and all under oath identified the pictures as being that of their son and brother. The pictures were then shown to other friends, and by a large number of them identified as the picture of Frederick Adolph Walters. Several parties at and near Lawrence, where Walters worked, recognized the pictures as those of Walters. Mrs. Gilmore, daughter of the proprietor of the Central Hotel, where Walters was sick, identified the pictures positively. All members of Walters's family swore that he had very dark- brown hair, a wide forehead, a broad German face, an aquiline nose, long hands, and extraordinarily sound teeth. He was also described as being well built, a skillful Turner, and five feet eleven inches high. He had no scars on his body except a small one, half as large as a pea, near one ankle, caused by the bite of a dog. This scar was last seen when Walters was twelve years old ' a sister so testifying. He had a mole on his back. This description was exactly that of the dead man, except as to the small scar. No such scar was discovered, as Dr. Miller examined the body with a magnifying glass, and found no scars on it except a slight one on one finger. Walters was a young man of excellent habits and strong social attachments. He was on the best of terms with everybody, and had no known motive for leaving home, except for the purposes testified to and indicated in his letter to Miss Kasten.

(Comment.) ' The facts are that Hillmon and Walters disappeared simultaneously. One of the two reappeared dead. The bulk of the evidence shows that the dead man was not Hillmon ' that it was Walters; that Hillmon had every motive to prevent his reappearance, if alive ' desire to secure the insurance money, and an equal desire not to go to the penitentiary; and that Walters, if alive, had every motive to induce his return. The letters written from Wichita by Walters were admitted by Judges Foster and Brewer, but were ruled out on the last trial by Judge Shiras. The Walters sisters were both kept away from the last trial by the death of their mother, and the serious illness of other members of his family.

General Notes and Considerations.

' There has been much talk about the presumption of death in law after the lapse of seven years as being a proper dependence for the plaintiff. This could not be, as the question is not whether Hillmon

========== Page 877 ========== is now dead, but whether he died at the date of the killing at Crooked Creek; in other words, whether the proofs of death made by Mrs. Hillmon were good.

The five

========== Page 878 ========== have been a Christian gentleman. But he is charged with a terrible crime ' lifelong banishment, self- inflicted, from wife and kindred and friends for a few paltry dollars that he himself could never enjoy.

Mr. Wheat turned to the question of identity. The policies all put Hillmon at five feet eleven inches, but a statement is introduced that Hillmon went back to Dr. Miller, one of the examining physicians for the companies, and said he was only five feet nine inches. But the policies were never changed in that particular. These policies, these silent witnesses that the agents of the companies themselves afford, are strongly corroborated by the oral testimony of Mrs. Hillmon, who measured him, and found him five feet eleven inches, the same height as the body brought to Lawrence.

Mr. Wheat asserted that the letter from G. W. E. Griffith, the insurance agent, to Mrs. Hillmon, soon after the death of her husband was reported, asking her to call and make out an application, and Griffith's questioning of her, aided by Selig, another insurance agent, were for the purpose of puzzling her in her distressed state of mind, and getting her to make statements that could be used to beat her out of the insurance. Then later on they plied her with reasons why she should not see her husband, in an effort to destroy a witness against themselves.

Mrs. Hillmon, Arthur Judson, Levi Baldwin, John Brown, and six other Lawrence witnesses, who knew Hillmon well, testify that the body was his. A half dozen Medicine Lodge to the place of the accidental killing, and the two men were Hillmon and Brown.

The photographs of Hillmon and the body were placed in the hands of a jury, and attention called to the decomposition in the nose of the body in just the spot where Dr. Simmons had testified that he had treated Hillmon for an injury. Dr. Fuller testified that the nose of the body had the appearance of having been injured in that spot, and it has been shown that decomposition took place more rapidly in injured parts.

The vaccination of the arm of the body, it is claimed, was not so far along at the time of death as it should be on Hillmon, but this matter of telling the age of a vaccine sore is very uncertain at best, and the fact that the arm of the body was vaccinated in exactly the place where Hillmon was vaccinated is another strong piece of evidence in the plaintiff's favor. The insurance company's physicians carried away the scab and piece of the arm upon which it was, and now it cannot be found. It looks like suppression of evidence. At any rate, they ought to admit that the matter of vaccination is all right. The hair of the body was dark brown. So was Hillmon's. Walters's was bluish black. The temples of Walters were bare. Hair grew on Hillmon's temples, and there was hair on temples of the body. There was a scar on Walters's leg, where he was bitten by a dog. No such scar was found on the body. The body was so badly decomposed that the identification of it by the Walters family by photographs of it is out of the question. The hair on the body was fine. So was Hillmon's. Walters's was coarse.

The tooth feature of the testimony is very uncertain and unreliable. Some of the witnesses may have honestly imagined that Hillmon had a tooth out, but they were mistaken. None of them stand the test of questions in regard to other people's teeth. People who know the worth of testimony have no confidence in that offered about Hillmon having a tooth out. The same industry and expenditure put forth to get up this

========== Page 879 ========== tooth testimony by the defense would have produced Hillmon had he been in the land of the living, and especially had he been in New Mexico, where they say he has been.

Argument by John Hutchings. ' Mr. Hutchings said that the plaintiff had proved by John H. Brown, the person best qualified, that Hillmon was killed; by Mrs. Hillmon, the widow, the next best qualified person, that the body was that of her husband; by Levi Baldwin, the most intimate friend of Hillmon, that the body was Hillmon's. Five Colonel Walker was too swift a witness. He could remember about Hillmon's tooth, but he could not tell which leg B.J. Horton had lost, though he has known him and seen him almost every day for many years. W.W. Nichols was a wretch who came here from Washington county for $148 and fees and expenses to give testimony calculated to make his wife's brother a murderer. He excoriated Tillinghast, Selig, and Griffith, the insurance agents, for attempting to entrap Mrs. Hillmon into a description of her husband before his body arrived. These insurance companies, with boundless wealth and inexhaustible resources at their command, with agents scattered the world over, with six years to operate in, have failed to find Hillmon. They bring depositions from New Mexico, from a worthless class of fellows, instead of bringing Hillmon. Dr. Miller produces a remarkable account book, which, though not intended for that purpose, contains memorandum of Hillmon's height, dated December 17th, according to which he was five feet nine inches. Dr. Stuart testified that Hillmon afterwards came to him, and gave his height as five feet eleven. Hillmon must have been a marvelous man. One of a party of three, traveling through a settled country, camping out, and stopping at houses, he succeeded in concealing one of the party through the entire journey from Wichita to (See State of Mind: The Hillmon Case, the McGuffin, and the Supreme Court by Marianne Wesson for a discussion of the Kasten letter's importance in the Hillmon Case.)

========== Page 880 ========== Argument by Samuel A. Riggs. ' Mr. Riggs called attention to the difficulty Mrs. Hillmon has had in the prosecution of this case in her poverty for five years. He characterized the taking of the insurance at Lawrence by Hillmon as an ordinary transaction of life insurance. Hillmon was of good character, and in good circumstances. It has been asserted that he mortgaged his life to the payment of premiums on a large amount of insurance. It is not unlikely that he intended to permit the policies to lapse after his trip to the Southwest. As to his financial circumstances, he was for many years in the hide business in Texas, when it was profitable. He afterwards fed 250 hogs at Wyandotte. His trip was a natural one, made at a proper time, as southwestern Kansas is a winter stock country. The Indians had raided western Kansas in September, and in the following winter he very naturally protected his young wife by insuring his life. Riggs read the account of the killing as it appears in Brown's deposition. Brown, he said, had stood up for four years in the face of the law, and asserted that his first account of the killing was true. He was here three years ago, and gave his testimony. The defense in this case was purely one of suspicion, beginning with the untrue assumption of poverty and a reckless life on the part of Hillmon. A remarkable feature of the case and one strongly in favor of Brown, is that ever since the so-called coroner's inquest at Lawrence, the defense has been in possession of a detailed statement of Brown's as to the trip that he and Hillmon had made; where they went; where they stopped; and the names of families and persons whom they met. This has never been produced in court, and for a good reason; the defense has never been able to show that at any time, anywhere on that trip, there was a third man in the party besides Hillmon and Brown. With all their money and all their power they have never been able to find a vestige of Hillmon. Five witnesses at Medicine Lodge, when the body was taken up, was the cutting open of the coat- sleeve, and finding the vaccination mark. Now, mark you, as soon as the body arrived at Lawrence it was taken possession of by the undertakers, and almost the first thing was the cutting out by the physicians of the company of the pieces of flesh in the arm on which were the vaccination scabs. It was carried away, and afterwards could not be found. Under these circumstances, it would be but fair for the defense to concede that the vaccination was all right.

Mr. Riggs spoke of the action of Griffith, Selig, and Tillinghast as a trap purposely set for Mrs. Hillmon. They tried to weaken her case by inducing her to make some statement in the description of the body which they could use against her afterward. Then the evidence of John H. Brown had to be disposed of. Brown's whole conduct bore out the theory of innocence. He stayed with the body at

========== Page 881 ========== it was a studied attempt on the part of the insurance companies to destroy Brown as a witness for Mrs. Hillmon. We have been asked why we did not take Al. Baldwin's deposition. Look at Brown's deposition here. He was cross-examined for nineteen days. That was a notification to us from the defense that we were not to be allowed to take any more depositions. Mr. Riggs did not think it remarkable that a poor, weak woman, confronted by the statement of Brown, rendering him worse than useless as a witness for her, and in the hands of a shrewd attorney like Buchan, should be induced to release the policies. A strong point, and one that destroys the Walters theory with evidence in which there can be no mistake, is the fact that Walters's temples were absolutely bare, while those of Hillmon had hair on them corresponding with the temples of the body, as shown in the photograph and testified to by Lamon, the photographer.

In finishing, Mr. Riggs urged the jury to mete out justice to the plaintiff, and nothing more, in the unequal contest which she had sustained with these great and powerful corporations, the insurance companies.

ARGUMENTS MADE BY COUNSEL FOR DEFENDANTS.

Argument by J.W. Green. ' Mr. Green urged that it was not incumbent upon the defense to show that the body was that of John W. Hillmon, whose life, was covered by the policies. The companies are worth millions. This $25,000 is not a drop in the bucket, and would hardly be worth contending for if it was not for the fact that it involves conspiracy, fraud, and coldblooded, atrocious murder. Hillmon was a wild, roving fellow. He herded cattle out here in Leavenworth county, went to Texas and Colorado, and drifted aimlessly about for years. Then he suddenly took a notion to have $25,000 insurance on his life. The premiums amounted to $600 a year ' more than the average man earns, more than Hillmon was ever known to earn. He mortgaged his life for that sum, poor though he was. He sought the insurance, was anxious about the policies, paid a portion of the first year's premium, suddenly disappeared, was reported killed and buried. The men whom Mrs. Hillmon says she sent after the body fenced the grave and started away, when they were required by the insurance companies to take the body up. It was brought to Lawrence. The alleged widow did not go to see it for three days. She kept away from it until she feared the effect of her action would prevent the success of the conspiracy to defraud f the companies out of $25,000, and then she went to see it. Colonel Walker saw the body at

========== Page 882 ========== Green said that any number of men who do not know that a tooth is missing cannot equal one witness who does. Hillmon's schoolmates and boyhood acquaintances swear that he had a bad front tooth and the relatives and acquaintances swear that later in life he had lost that tooth. As to the vaccination, competent physicians who examined the scab on the arm of the body say that it could not have been older than 19 days, and from all appearances was only 14 days old. Yet Hillmon was vaccinated February 25th, and killed March 18th. If Walters was vaccinated at Wichita about the time of leaving there with Hillmon, the scab on the arm of the body would correspond with the scab on Walters's arm at the time of the killing, so far as age is concerned. At Lawrence Mrs. Hillmon said that the body was that of her husband, but six months later she confessed that it was not, by giving Mr. Buchan releases of the policies.

Was it the body of Walters? So his own family testify, and one of his sisters, Fannie Walters, bears a striking resemblance in features to the face of the cadaver. Those sisters testified by their tears and grief as well as by their words. Mr. Green read the letter from Walters to Alvina Kasten wherein he says that he was going southwest with Hillmon. No one had questioned the genuineness of the letter. The ring mark on the finger of the body which the plaintiff's attorneys' had tried to make a point on was in all probability the mark of the ring that Alvina Kasten had testified that she gave him when they parted. Walters is traced from his home at Fort Madison to Wichita, and from that point writes a letter saying that he is going away to the southwest with Hillmon. After that he is never heard of. A body answering in description to his is produced, and his relatives and friends testify that it is his, and still we are asked to regard these as a series of coincidences meaning nothing and proving nothing. Walters was five feet eleven inches in height, had dark-brown curly hair, high cheek bones, a Roman nose, light mustache, perfect teeth, was muscular, had long bony fingers and large feet. That is an excellent description of the body of the man mysteriously killed and hastily buried at "photograph gallery" and the fancied resemblance between Hillmon and the cadaver, and pointed out the similarity between the cadaver and Walters.

(See A Digital Photographic Solution to the Question of Who Lies Buried in Oak Hill Cemetery by Dennis Van Gerven for a comparison and analysis of the photos of Hillman, Walters and the corpse in the Hillmon Case.)

Argument made by George J. Barker. ' Mr. Barker said he believed the original plan and object of the first trip made by Brown and Hillmon in December was to find a dead body that could be passed off for that of Hillmon. This failed, and another plan was adopted, which was the murder of Walters and the palming off of his body for that of Hillmon. Mr. Barker bore down with considerable stress on the letters written from Wichita by Walters to his intended and to his sister, wherein he said he was going away with Hillmon. What did Hillmon want of Walters? Walters had no money and no stock. Hillmon had no use for him except the terrible purpose for which he did use him. The three men did not leave Wichita together. Brown testifies that three or four miles from Wichita they picked up a man. This man in all human probability was Walters. The second trip to Medicine Lodge consumed much more time than the first. It was on this trip that Walters was prepared for slaughter. He had to be vaccinated. That was prob-

========== Page 883 ========== ably done in the camp on Cowskin. In a covered wagon with one seat a third man could easily be concealed. There were few people along the route to see them. They stopped in lonely places. Mr. Barker called the attention of the jury to the diary taken from the pocket of the dead man, from which he read, and said it had evidently been written to read and to be the means of identifying the person upon whom it was found as John W. Hillmon. Two days after the killing, Brown coolly writes to Mrs. Hillmon, tells her he has killed her husband, and asks what he shall do with the ponies. Here is a man who carries $25,000 on his life; he is buried at Medicine Lodge a week. Levi and Al. Baldwin come down there. They do not take the body up, but build a fence around the grave of this man with $25,000 insurance on his life. The hat had been burned up when the killing occurred; the shoes were lost on the way to Hutchinson. These two important articles of identification were thus disposed of. The body was taken up at the instance of the insurance companies and taken to Lawrence, where people who knew Hillmon might see it. In regard to the tooth and height testimony, Mr. Barker said that it was not possible that Colonel Walker, Dr. Miller, Ollie Walker, Hillmon's sister and brother-in-law, could be mistaken. In describing the missing Fred Walters, the Walters family had described the body almost exactly. Hillmon and Brown were three months trying to find a cattle ranch. No question of identity was raised at the Barber county inquest. Updegraff, the hotel keeper, who thought he knew Hillmon, and who evidently did know him as well as any of the

========== Page 884 ========== Mr. Barker closed with an appeal to the jury to do justice as between corporations and a woman. He hoped they would not allow their sympathy to be played upon at the expense of equal and exact justice.

Argument by Charles S. Gleed.' A man's acts must be construed by the light of his motives. In considering what he does it is necessary to look further ' for his motive in doing it. And, conversely, in assuming a motive we must look further to see that the resulting act is in accordance with it. No test will more surely crush the body of any friend than this test of motive. Now let us see briefly what effect this test has on the case in hand.

What was Hillmon's motive in settling on his life an insurance of twenty-five thousand dollars? He was little beyond 'passing rich with forty pounds a year.' Sixty dollars a month for insurance was beyond his depth. Could he have had the slightest expectation of dying immediately? Could he have had the slightest expectation of keeping up his payments? And here let me call your attention to the fact that this insurance was effected on what is known as the "Tontine" system ' by all odds the worst system for a poor man, as by the failure to pay any given premium when due, the whole policy lapses, and the payments are forfeited. I ask you, Can you ascribe any motive to this extraordinary proceeding other than the motive of fraud?

What was Hillmon's motive in going, in the dead of what he has himself described as an unusually cold winter, into the empty spaces of western Kansas? He says he went to look for a stock ranch. Have you any such belief? Would you do the same thing? Would you drive day after day over the bleak prairies of western Kansas next January looking for a stock ranch, having no money to buy with if you found one? If you were looking for a stock ranch, would you travel miles and miles along the Santa Fe road? I ask you can you ascribe any motive for this unusual proceeding other than the motive Of fraud?

What was Hillmon's motive in writing this peculiar diary which has been read in your presence? It takes this man thirty odd years to discover that he needs a diary. He begins suddenly, writes briefly, ends suddenly, and with great formality signs his name to the document, and then carries the book for a considerable time without apparent reason. Was not this book written to be found on the body of the murdered man? Can you discover any motive in this unusual proceeding other than the motive of fraud?

What is Hillmon's motive, if he is alive, in keeping out of sight? The instinct of self-preservation will keep him hidden forever. An outraged public yearns for him, and those whom he has attempted to defraud have set a price upon his head.

What was Brown's motive in so precipitately burying the body of his friend at Medicine Lodge when the coffin was opened, has never been called upon to testify. The second prefers the jungles of Arkansas to the witness stand in Kansas. He makes a better appearance in the pages of a tediously-taken deposition than he would on the witness stand under the scrutiny of your

========== Page 885 ========== eyes. Alva Baldwin knows that the body he saw at Colonel Sam'l Walker and his son, to Hon. J. W. Green, Dean of your State's University

========== Page 886 ========== Law School, the then County Attorney of Douglas county ' what motive do you ascribe, I say, in their conduct of the coroner's inquest, their treatment of the cadaver, and their subsequent efforts and evidence on behalf of the defense? These men are above reproach in their private characters; they are leading churchmen, leaders in society, honorable soldiers, and good men by whatever test they are examined. Dare you, by giving a verdict for the plaintiff, brand these men as perjurers and conspirators? Dare you say that for thirty pieces of silver, by the sum more or less, which they might receive from the insurance companies, they would blacken the whole record of their lives by an infamous proceeding like this? Dare you ascribe to them as a motive for all they have done, avarice and cupidity?

What motive has Frederick Adolph Walters for remaining hidden? Father, mother, brother, these sweet sisters whom you have seen here, a lover - these call him, if he be alive, from his hiding place, and demand his appearance.

What motive had William J. Buchan in his connection with the matter? This man who has been twelve or fifteen years in the State Senate, and who has made more of the laws of this State than perhaps any other man in it; who has for his friends and admirers the leading men in the State; whose money and business are ample; whose public and private life have never been impeached ' this man could not have had the motive ascribed to him by the counsel for the plaintiff, the motive of getting a small fee in return for robbing a widow and extracting perjury from his client. The idea is an insult to your intelligence.

What motive have the insurance companies in beginning and continuing this contest? None, I submit, but that of a desire to defeat an attempted fraud. A reputation for being poor pay is a thing which no insurance company can stand. To advertise to the world that it will always contest a claim where it has a shadow of ground on which to make such contest, is to drive any insurance company out of business. The trouble and expense of this litigation, added to the undesirable advertisement which such litigation gives, far overbalance the amount directly involved. The only motive which the companies can have in prosecuting this case is that of discouraging the sort of crime of which this is a sample, and which today is one of the most prevalent of all forms of fraud. In both life and fire business the gravest frauds are attempted daily. In Kansas, the fraud on life insurance companies (including the Hillmon cases) are best exemplified perhaps by the Winner and McNutt case, these two men being now in the penitentiary for burning one Seiver in a house at Wichita, the body being passed off as that of McNutt, who was insured. It is a notable fact that this affair was invented in Leavenworth county, only a few miles from the home of Hillmon and Baldwin. Near Leavenworth lived a man at least up to three years ago, who was supposed to have jumped from a boat on the Hudson river and drowned, and to whose widow the insurance money due on his life was paid; for fourteen years that man lived quietly and securely within a few miles of the city. The case of Jacob Smith, of Atchison, who set fire to his packing houses for the insurance, is remembered by all. In the little town of Eudora, Douglas county, some five years ago, a Dr. Clause insured his house and its contents for three thousand dollars. The property was burned and heavy insurance was paid over, but the finding of a watch, which was scheduled as lost, aroused the suspicion of interested parties, and enabled George J. Barker to force from the doctor a confession and a complete restoration. The

========== Page 887 ========== whole property insured was worth four hundred dollars. Not long ago the Travelers' Insurance Company, of Hartford, Connecticut, had a case where a man secured heavy insurance on his life, built him a small workshop or laboratory in the vicinity of Baltimore, where he was one day, so the papers said, elaborately and completely cremated. From a certain suspicious circumstance the company contested the case, and for three or four years braved the indignation of honest people generally, who believed the death to have actually occurred. Finally, as a result of a quarrel between the supposed dead man on the one hand and the wife of a mutual friend on the other, the man put in an appearance and all parties were punished. During all the time of this conspiracy the supposed dead man was but a few miles' distance away. These very brief illustrations are sufficient to clearly point out the fact, for fact it is, that no one interest in our country to-day is so persistently beset by plots and conspiracies as the insurance interest.

JUDGE BREWER'S CHARGE [at the second trial].1 ' Gentlemen of the Jury: I congratulate you that this case is drawing so near to its close. And I congratulate the parties in this case that they have been permitted to try their case before such a jury. I repeat no idle compliment when I say that it has been a common expression of the many, who from time to time, have visited this court room during this trial, that we have an exceptionally fine, intelligent jury to try this case. Some of you are men of state reputation for character; all of you are men of mature years. Some of you have got beyond the meridian of life, and none of you can afford to barter your own self-respect, the character which you have earned and well earned in this state, for the mere paltry desire to please or favor one party or the other. At the outset I need no more than state that this case is one of peculiar interest. The many who, from time to time, have gathered here to listen to the testimony as it has fallen from the lips of the witnesses, indicate that there is an interest outside of the mere question of pecuniary interest to the parties, that there is a curiosity and a feeling which has brought them here to listen, and yet of them all who have been here from time to time, or who may have read in the papers the story detailed by these various witnesses, of council, witnesses, and parties, you and I are the only ones who, hearing all the testimony and the arguments of council, the whole detail of this case from its inception to its close, have looked at it or could have looked at it with the single thought that it is for us to settle what is the very truth of this controversy. It has developed before you that this case has run many years. The amount of the controversy, the interest that is felt, all compels, if possible, a verdict, a decision at this time. But while it is for the interest of all that if possible this question should now be settled, it is far more important that each individual juror should be loyal to his own convictions. It matters not what casual remarks you may have heard dropped from outside parties, or what you may have seen in the papers. The question comes home to you, and should come home to each one of you, that "I and I alone have listened to this story as told by these various witnesses, and that no man but myself is responsible for the verdict which must be rendered." I deem it not inappropriate to say that I shall feel it my duty to keep you together a reasonable time for consideration, deliberation, and the weighing of this testimony, but I

Footnote to page 887: 1. A newspaper report of the charge was supplied for this work, by courtesy of Mr. Gilbert Porter, of the firm of Messrs. Isham, Lincoln, and Beale, of the Chicago Bar. ' ED.